A selection of pieces by Matt Tyrnauer from various publications. Tyrnauer's work has appeared in Vanity Fair, The New York Times, Departures, Vanity Fair Italia, Vogue China, Numero and many other publications worldwide.

"O Brother, Where Art Thou?" - Vanity Fair, October 2008

I am standing with the architect John Pawson on a snow-covered ridge in Bohemia, two hours outside of Prague, somewhere between Pilsen, in the Czech Republic, and Marienbad, the famous spa town near the German border. We are in a cemetery—or what will be one—and 50 feet away is the massive hull of Pawson’s latest creation, a Trappist monastery called Our Lady of Novy Dvur (New Square, in Czech). It is late March, and ice cracks under our feet as we walk toward a tall wooden cross at the center of the graveyard. “I tried to hide the cemetery at first,” says Pawson, “but when the monks noticed that, they were unhappy and asked to have it put where they could see it from the cloister. For them, that is the best part: they get to go to heaven.” Learning to think like a monk was a big part of this commission for Pawson, 57, a native of Yorkshire who lives in London and is known for his pristine Minimalism. “When I told the monks this was a lifetime project, they became terribly upset, because they thought it was going to take forever. But now they understand that I will keep coming back only because there will always be something to get done,” he says. “They have limited funds, but their attitude is ‘God will provide.’ And I have been amazed that whenever they have needed money it has been there. At some points, admittedly, their priorities are different than mine.” | MORE |

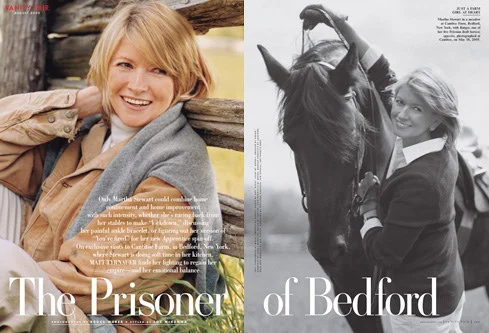

"The Prisoner of Bedford" - Vanity Fair, October 2009

I'm standing in stocking feet in the pantry of Martha Stewart’s house, where shoes are verboten in deference to highly polished antique-fir floors. An industrial-size Cimbali espresso machine is hissing in the background. One of the two Chinese housekeepers named Lily— Lily One, in this case (Lily Two is usually called Penny, to avoid confusion)—is frothing milk for cappuccinos. Stewart has just come downstairs, dressed in an orange polo shirt and orange Capri pants. On her feet are gold clogs—she is clearly exempt from the no-shoe rule—and on her right ankle, very much in view, is the black electronic monitoring device she is forced to wear. It looks like a Braun travel alarm clock attached to a cheap plastic watchband. Even before her first sip of coffee, Stewart is full of energy and shockingly forthright. “I hate lockdown. It’s hideous,” she announces to a group gathered in the pantry; the group includes Susan Magrino, her publicist, Julia Eisemann, her executive assistant, and Charles Simonyi, the billionaire software mogul and former Microsoft executive who is her sometime beau. Her ankle bracelet, unlike the canary-diamond studs in her ears, is an accessory she would love to lose. “I know how to get it off,” she confides to me at one point, causing Magrino’s eyes to widen with alarm. | MORE |

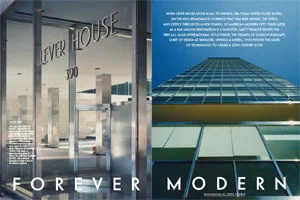

"Forever Modern" - Vanity Fair, June 2010

In 1952, the last year of Harry S. Truman’s administration, when only three percent of the American public traveled by plane and only 34 percent had TV sets, Lever House looked as if it had dropped from the sky onto Park Avenue across from the Racquet and Tennis Club and the grand old Montana apartments. Its elegant glass-and-stainless-steel slabs—a horizontal one set over columns on an open ground floor, and a vertical one perched as if floating above it—were quite unlike anything New Yorkers had ever seen. By day the structure shimmered in the sunlight and reflected the brick and limestone buildings around it. By night it lit up like a taut rectangular lantern—a vision of the future on a block between 53rd and 54th Streets. For weeks after Lever House opened its doors in April, curious citizens lined up to enter its airy lobby for a closer look. The architecture critic Lewis Mumford noted that the public was acting as if the new soap-company headquarters were “the eighth wonder of the world.” The Glass House, as the press called the building—so different from the sooty brick and limestone ziggurats of New York’s previous architectural generations—became an instant icon. Two decades of economic hardship and war had recently drawn to a close. In those years no significant buildings, with the exception of Rockefeller Center, had been constructed in New York. But now the economy was starting to roar, and the greatest building boom in the nation’s history was under way. | MORE |

"Architecture in the Age of Gehry" - Vanity Fair, June 2010

In February 1998, at the age of 91, Philip Johnson, the godfather of modern architecture, who 40 years earlier had collaborated with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe on the iconic Seagram Building, in Manhattan, traveled to Spain to see the just-completed Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. He stood in the atrium of the massive, titanium-clad structure with its architect, Frank Gehry, as TV cameras from Charlie Rose captured him gesturing up to the torqued and sensually curving pillars that support the glass-and-steel ceiling and saying, “Architecture is not about words. It’s about tears.” Breaking into heavy sobs, he added, “I get the same feeling in Chartres Cathedral.” Bilbao had just opened its doors, but Johnson, the principal apostle of the two dominant forms of architecture in the 20th century—Modernism and Postmodernism—and the design establishment’s ultimate arbiter, was prepared to call it on the spot. He anointed Gehry “the greatest architect we have today” and later declared the structure “the greatest building of our time.” Five years after Johnson’s death, in 2005, Vanity Fair has asked 90 of the world’s leading architects, teachers, and critics to name the five most important buildings, monuments, and bridges completed since 1980, as well as the most significant structure built so far in the 21st century. The survey’s results back up Johnson decisively: of the 52 experts who ultimately participated in the poll—including 11 Pritzker Prize winners and the deans of eight major architecture schools—28 voted for the Guggenheim Bilbao. That was nearly three times as many votes as the second-place building received. | MORE |

"To Have and Have Not" - Vanity Fair, February 2011

The apartment is cavernous, on a high floor of the Dakota, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Huge windows overlook Central Park, 30 feet above the tree line, with the grand residential buildings of Fifth Avenue in the distance. My meetings with Lauren Bacall, who is 86, are at three P.M. in the winter, so the light is silvery blue in the wood-trimmed parlor, where Bacall has set the scene for our sessions. A tall wooden chair, for her, is positioned in the center of the room, near a low, white-and-green-upholstered club chair, for me. A single lamp burns in a distant corner. She is dressed, every time, in a black shirt, black pants, and black orthopedic shoes. She always has with her Sophie, an excitable papillon, and what she refers to as “my friend,” her aluminum walker, with tennis balls on its feet. The “fucking fracture that I’ve got on the hip” is the result of a bathroom fall a few months back, a frustrating how-do-you-do after a life of near-perfect health. “Can you imagine? It’s the only time I have been in the hospital except for the times when I gave birth,” she says. A fighter by nature, Bacall has begun to venture out, supported by her walker, onto 72nd Street, going alone to physical therapy, for the most part unrecognized, just another senior citizen. “People don’t pay any attention to me or the walker,” she says. “The other night I was going into a doctor’s office, and some son of a bitch came out of the building, almost knocked me over. I said, ‘You’re a fucking ape!’—screaming at him. He never even turned around. Couldn’t care less, this big horse of a man.” | MORE |

"Once Upon a Time in Beverly Hills" - Vanity Fair, February 2011

On March 20, 1990, in the middle of the night, paramedics were called to the de Cordova home at 1875 Carla Ridge Road, in the Trousdale section of Beverly Hills. Freddie de Cordova, the executive producer of Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, and his wife, Janet, a leading local socialite sometimes referred to as the Duchess of Trousdale, were asleep in their separate bedrooms. The problem was downstairs, in the servants’ quarters, where Gracie Covarrubias, the longtime housekeeper, was trying to revive her husband, Javier, who was dying of a heart attack. When the paramedics arrived, they muted their sirens. Javier was removed on a gurney and driven to Cedars-Sinai hospital, where he was pronounced dead. Early in the morning, Gracie Covarrubias returned to the house, and at eight o’clock Freddie de Cordova appeared at the breakfast table. | MORE |

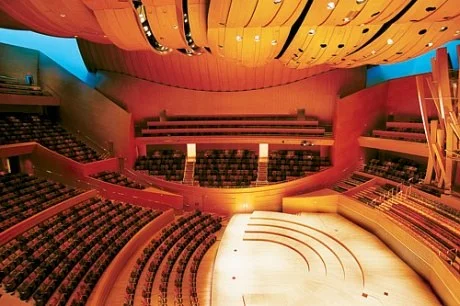

"Roll Over, Bilbao!" - Vanity Fair, February 2012

Frank Gehry drives his black BMW slowly along Grand Avenue in downtown Los Angeles. The street is torn up for the construction of a huge stainless-steel-clad building, which looks from this side like a futuristic sailing ship. Gehry scrunches down in his seat so that he can see the entire eastern façade of his $274 million Walt Disney Concert Hall, which is set to open this October as the new home of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. It will be one of the defining monuments of the 74-year-old architect's career. “‘Wow! Did I do that? Holy shit! Did I do that?’ Sometimes you look at it that way,” Gehry says, taking in the flowing ribbons of steel at street level and then gazing up at the luffing “mainsails” at the center of the building—forms which seem to defy engineering, and which were conceived by Gehry as squiggly lines on a piece of paper more than 16 years ago. “I haven't seen this side of it lately,” he adds. “When they take all the cranes and construction shit away, it's going to look nice.” Gehry, probably the most famous architect in the world right now, and arguably the most important and influential, is a modest figure in a profession known for its massive egos. He habitually dresses down: white oxford shirt, chinos, loafers, and a beige windbreaker. Short, with a shock of white, unruly hair, he often wears a bemused grin, and his face is soft and kind. Friends and associates call him “Foggy,” a play on his initials, F.O.G. (the O is for Owen). | MORE |

"Vidal's Ravello Redoubt" - Vanity Fair, August 2012

Gore Vidal, who died at his home in the Hollywood Hills on Tuesday at 86, was always perturbed when the press referred to him as an expatriate. Vidal spent most of every year, starting in the early 1960s, in Rome, and later between Rome and a grand villa, La Rondinaia (the swallow’s nest), in the Amalfi Coast village of Ravello. He preferred to think of his position in Southern Italy as a perch from which to observe his country. I think the scores of novels, essays, and plays he wrote about the United States prove that the distance gave him great perspective on what he variously referred to as the United States of Amnesia and “my only subject.” Federico Fellini, whom Vidal befriended in Rome—Vidal appeared as himself in Roma and wrote a draft of Fellini’s Casanova—said that Gorino, as Fellini called him, had “gone native” in Italy. Vidal rejected that pronouncement as well, and, indeed, his grasp of the Italian language was always rudimentary at best, in keeping with the much-preferred role of American Icon Abroad, which he played in the manner of the movie stars who frolicked together on the Via Veneto at the time of La Dolce Vita. (I imagine he thought of himself as possessing the star power of an Elizabeth Taylor trapped in the body of a Burt Lancaster.) | MORE |

"Flight of Imagination" - Vanity Fair, February 2014

The Wind Rises, director Hayao Miyazaki's latest—and, he says, last—animated feature, has sparked controversy on many fronts. The film is the fictionalized story of airplane engineer Jiro Horikoshi, who designed the Mitsubishi Zero fighter, used in the attack on Pearl Harbor. Miyazaki, widely considered the greatest of animators—Spirited Away won an Oscar in 2003—is a pacifist, and his rich, sensitive epic film has raised the hackles of political conservatives in Japan, who want a return to militarization, as well as in the U.S., where any celebration of the design process of one of the most efficient killing machines of World War II has been questioned. “The film grapples with issues of war and peace, and Jiro's world was moving in a dangerous direction, as ours is today,” says Miyazaki, adding, “I did not want to deny that world. Jiro lived in the 1930s and was one of the most gifted engineers of his time.” | MORE |

"Naming the Miami Skyline" - Departures Magazine, September 2014

Today it's practically impossible to name a world-class architect without a presence in the city: Frank Gehry, Zaha Hadid, Rem Koolhaas and Norman Foster are among those behind a building boom that stretches from Sunny Isles to Coconut Grove. Modern architecture was all about rejecting history and starting with a clean slate. Miami—variously called “the city of the future” and “the city without a past”—has for this reason been an ideal proving ground for many a would-be visionary with an edifice complex. In 1896, when Henry Flagler’s Florida East Coast Railway reached the swampy landmass on Biscayne Bay (an area so unexplored the botanist John K. Small called it “the land of the question mark”), the exotic wilderness began its forced transformation into a fantasy of the tropics, fueled by the dreams of speculators, developers, marketers, hucksters, mobsters and a long line of usually unsung architects who have ridden the epic booms that have defined the city, leaving marks as clearly defined as rings on the stump of a sequoia. | MORE |

(For more of Matt Tyrnauer's articles and publications, please visit matttyrnauer.com)